UK Energy Bills to Rise 14 Times Faster than Wages Amid Green Push, Sanctions War

By JACK MONTGOMERY

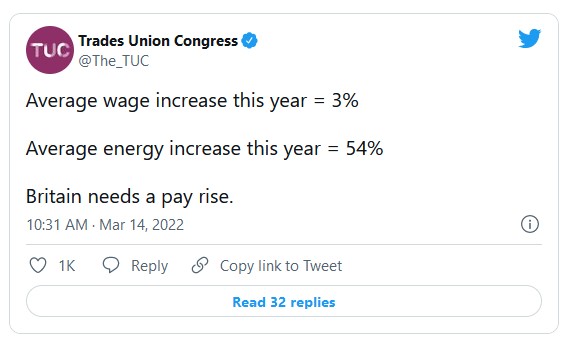

- British energy bills look set to increase some 14 times faster than British wages in 2022, the Trades Union Congress (TUC) has warned.

-

“[G]as and electricity bills are set to increase by 54 per cent when the price cap set by Ofgem is increased in April,” the umbrella organisation said at the weekend, referencing Britain’s Office of Gas and Electricity Markets regulator.

“[B]y contrast average weekly wages are set to rise by just 3.75 per cent per cent in 2022,” they added, suggesting that “record-high” bills could effectively wipe out people’s pay rises.

“[Y]ears of wage stagnation, and cuts to social security, have left millions badly exposed to sky-high bills,” commented the union body’s general secretary, Frances O’Grady.

“With households across Britain pushed to the brink, the government must do far more to help workers with crippling energy costs,” the trade unionist went on, suggesting a “windfall tax on oil and gas profits” and an increase in welfare benefits to tackle the crisis.

Britain’s oil and gas industry is not the cash cow it once was, however, with a notionally right-wing government increasingly obsessed with green policies and achieving “net-zero” having already allowed regulators to block the development of a major gas field in the North Sea.

Prime Minister Boris Johnson, going against his pre-premiership principles, has also continued the effective ban on the exploitation of Britain’s rich on-shore shale gas reserves instituted by fellow Conservative Party prime minister Theresa May — although Brexit minister Jacob Rees-Mogg has signalled that this may finally be reversed as the energy crisis worsens.

Gas and oil supplies are, of course, under severe strain as a result of the British sanctions war with the Russian Federation following President Vladimir Putin’s latest invasion of Ukraine — leaving Britain in the unenviable position of having to curry favour with the even more despotic Saudi Arabian regime in an effort to increase supplies, despite its having just boasted of beheading dozens of people in the largest mass execution for a generation.

A lax attitude towards energy security dogged the British governing class — or, more accurately, those they govern — long before the current crisis and the Johnson-era fad for green politics, however, with the country’s gas storage capacity being described as “pitifully low” by analysts.

Germany, which has its own issues with rising energy prices, nevertheless boasts 17 times the storage capacity of the United Kingdom, for the sake of comparison.

In 2017, the Rough gas storage facility under the North Sea — which accounted for an astonishing 70 per cent of the country’s storage capacity, more or less — was allowed to close down, with the government indicating that shortages could be met by bringing in gas from Norway, pipelines linked to Continental Europe, and liquefied natural gas (LNG) ships.

“There is still a level of complacency in the government that despite recent events the best course of action is to just accept these price shocks,” a consultant representing storage developers and industry associations told Reuters in 2018.