Special report: War, fever and baseball in 1918

By Kendall Baker, Jeff Tracy

In January 1918, the horrors of World War I were in their final year, and Major League Baseball was preparing for its 16th season. But beneath the surface, another deadly battle was brewing. They called it the "Spanish flu."

By the numbers: Over the next 15 months, the global pandemic infected an estimated 500 million people — about a quarter of the world's population at the time — and killed as many as 100 million.

In the U.S., more children under nine died in 1918 than during the next 25 years combined. In the span of 12 months, the average U.S. life expectancy dropped almost 12 years.

The big picture: In some respects, the coronavirus and Spanish flu aren't all that comparable. After all, the war provided a vastly different backdrop, little was known about viruses at the time (imagine having no idea what you were suffering from) and medicine was far less advanced.

"In 1918, the basic treatments that were offered were enemas, whiskey and bloodletting. Hospitals as we know them today were quite different. There were no intensive care doctors [and] no antibiotics to treat any secondary infection. So it was a very different time and a very different way of practicing medicine."

— Dr. Jeremy Brown, National Institutes of Health, per CBS

Yes, but: There are still plenty of lessons to be learned — and perhaps there's some comfort in knowing that our ancestors went through something similar and came out the other side, not only intact but literally "roaring."

2. The first wave hits America

In March, with the U.S. fully mobilized for war, soldiers at Camp Funston in Fort Riley, Kansas, began reporting acute flu-like symptoms.

"The most horrific symptoms were that you could bleed not only from your nose and mouth but from your eyes and ears. People were turning dark blue from lack of oxygen," John M. Barry, author of "The Great Influenza," told CBS.

The backdrop: Around this time, Congress passed the Sedition Act, making it a crime to say or publish anything that cast the government or the war effort in a negative light. So, as the virus began to spread, the nation wasn't told.

President Woodrow Wilson had also created the Committee on Public Information — a propaganda machine designed by Arthur Bullard, who once wrote, "Truth and falsehood are arbitrary terms. ... The force of an idea lies in its inspirational value. It matters very little if it is true or false."

The bottom line: During the spring of 1918, a strange wave of the flu hit America. There were deaths, but not enough to serve as a warning for what was to come, and the general response was: Take some medicine, rest and get back to work.

3. Baseball against the backdrop of war

Unlike in 1942, when Franklin D. Roosevelt's "Green Light Letter" urged baseball to continue during wartime, it was unclear if the 1918 MLB season would go on as planned.

Boston Braves catcher Hank Gowdy (pictured above, center) was the first MLB player to enlist, and by the time spring training rolled around, plenty more had joined him.

A month into the season, the government issued the "Work or Fight" rule, which stated that by July 1, all men with "non-essential" jobs must enlist, make themselves draft-eligible or apply for work directly related to the war.

Hundreds of players joined the military ranks, while others took jobs at mills and shipyards, which led to the rise of industrial leagues.

Bethlehem Steel lured big leaguers like "Shoeless" Joe Jackson to play in its six-team baseball league. "The whole gang of them was draft dodgers," said one umpire. "They were supposed to be working for the war, but they didn't do any work. All they did was play baseball."

Baseball was given a reprieve when the "work or fight" deadline was delayed two months. So, while the season would need to end in mid-September, at least it wouldn't be killed mid-stride.

With so many players having already left to aid the war effort, teams scrambled to replace them. Who left and who remained shifted the balance of power in baseball — and led to the rise of baseball's greatest legend.

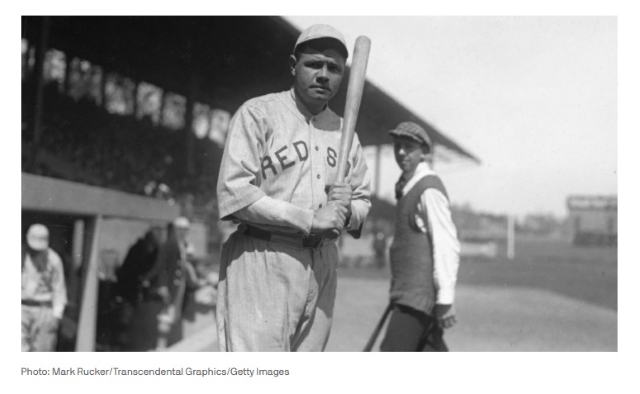

4. The rise and near-death of Babe Ruth

Amid war and influenza, the greatest hitter in baseball history was finally given an opportunity to, well, hit.

March: During spring training, the Red Sox held batting practice for the troops at Camp Pike in Little Rock, Arkansas, where a 23-year-old pitcher named Babe Ruth smashed five home runs. The next morning's headline: "Ruth Puts Five Over Fence, Heretofore Unknown to Baseball Fans."

Yes, but: Ruth's legendary power overshadowed a curious development: several Red Sox players had fallen ill. Reporters detailed their flu-like symptoms, but since so little was known at the time, no alarms were sounded.

April: In desperate need of hitters after losing some 13 players to the war, Red Sox manager Ed Barrow turned to his best pitcher, Ruth, who had won 24 games the year before (2.01 ERA), while hitting just two home runs.

During the "Dead Ball Era," most hitters chopped at the ball, aiming for singles. But Ruth swung for the fences, revolutionizing the sport and becoming baseball's first true slugger.

May: The Babe got the flu, and when the Red Sox physician treated him with silver nitrate, it only made things worse, causing him to choke and pass out. After being rushed to the hospital, there were rumors that Ruth was on his death bed.

Fortunately, he made a full recovery and got back to mashing. "The Great Bambino" hit 11 homers in May and June, more than five American League teams hit all year.

5. Warnings of a second wave

The shortened season ended with the Red Sox (75-51) narrowly winning the American League over the Cleveland Indians (73-54) and Washington Senators (72-56), while the Chicago Cubs (84-45) ran away with the National League.

HR leader: Despite pitching every fourth day, Ruth finished tied for the MLB lead with 11 dingers.

WAR leader: Senators ace Walter Johnson (11.7 WAR) finished 23-13 with a 1.27 ERA, 29 complete games and eight shutouts.

Hitting leader: Detroit Tigers CF Ty Cobb led baseball with a .382 batting average and a .440 on-base percentage. He also had 14 triples and 34 steals.

A warning: As baseball's regular season entered its final stretch, soldiers unknowingly infected with a new, far deadlier strain of influenza began arriving in port cities around the world. One of those cities: Boston.

"On August 27, when the Red Sox are wrapping up their final home stand at Fenway Park, there are reports from Commonwealth Pier in Boston that sailors are sick with influenza.

"And this isn't your ordinary flu. It's killing guys, their lungs are filling up with this foam, they're turning purple — it's something doctors have never seen before. Within a week, the disease had spread and sick civilians were overwhelming Boston hospitals."

— Johnny Smith, co-author of "War Fever: Boston, Baseball, and America in the Shadow of the Great War"

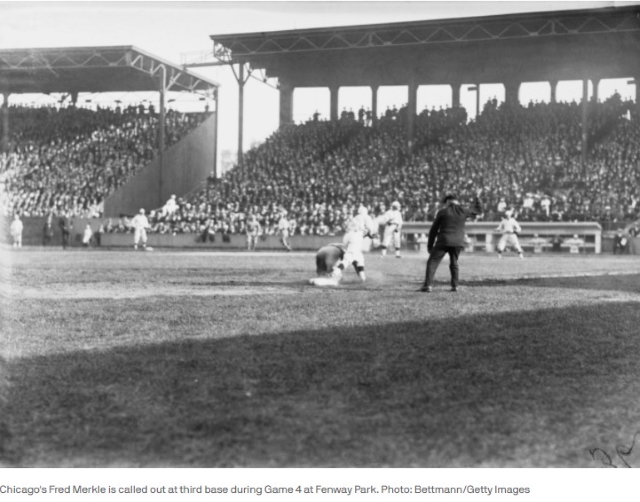

What came next: The World Series went ahead as scheduled, with the first three games set for Chicago and all remaining games set for ... Boston.

6. "The most joyless World Series ever"

Plenty of sports fans know who won the 1918 World Series, since it was the last Red Sox title before the infamous Curse of the Bambino took root. What they probably don't know is ... everything else.

Games 1-3 in Chicago: Ruth pitched (and won) Game 1, but was benched in Games 2 and 3 (which they split) to stay fresh for his Game 4 start. Yes, Babe Ruth was benched. In the World Series.

Fun fact: Game 1 marked the first time "The Star Spangled Banner" was played at a sporting event — a tradition that later extended to all sports after it became the National Anthem in 1931.

Trip to Boston: To save money, the two teams took the same train. While on board, they discussed holding out for more money (bonuses were based on gate revenue, which had plummeted due to the war, and the pool was set to be split with the top-four teams in each division for the first time).

Game 4: Owners refused to discuss pay, infuriating the players. Ruth pitched another gem, giving him 29.2 scoreless World Series innings to begin his career, a record he always said he was most proud of.

Game 5: Owners agreed to meet before the game, but they showed up drunk. While players were fuming, they also knew that if Boston won, they wouldn't be able to keep negotiating. Lo and behold, Chicago won, forcing Game 6.

Game 6: Tensions boiled over. Owners and players couldn't come to an agreement, and fans grew frustrated that baseball players were complaining about money during wartime. Boston won the game, and the series — but no one seemed to care.

"It was as anticlimactic as a game could be. No celebration in the stands. No celebration on the field. It was almost as if everyone was happy just to get it over with. Little did Red Sox fans know there would be another 86 years before they'd win another World Series."

— Skip Desjardin, author of "September 1918: War, Plague, and the World Series"

P.S. ... Rumors have persisted that the Cubs threw the series, with some suggesting it fed directly into the Black Sox scandal the following year.

7. The wrath of the second wave

The spring wave had been mild, but the Spanish flu came back in the fall with more than a vengeance.

Boston: By the time the World Series ended, Boston was in the midst of a public health crisis and residents began practicing what we refer to today as "social distancing."

But it was clear that city officials had waited too long, and that crowded public events — like World Series games — fueled the spread, ultimately infecting at least 20% of the city's population and killing nearly 5,000 Bostonians by the end of the year.

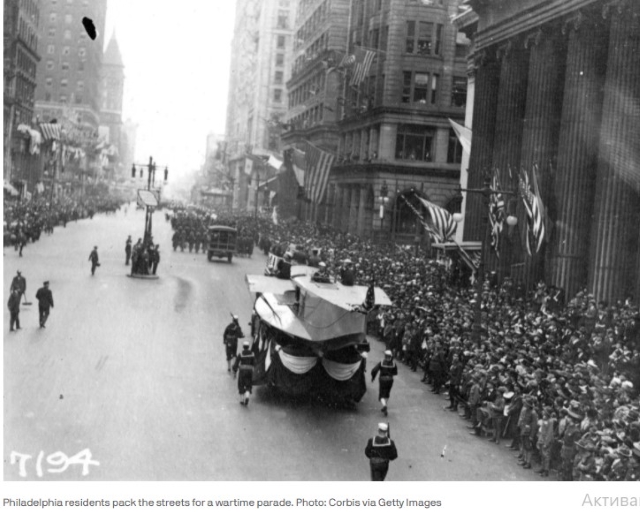

Philadelphia was hit even harder, thanks to city officials ignoring scientific experts and moving forward with a 200,000-person parade on Sept. 28.

Three days later, every hospital in Philadelphia was filled with sick patients.

By the end of the week, 4,500 were dead.

By the end of the second wave, nearly 18,000 Philadelphians had died of the flu.

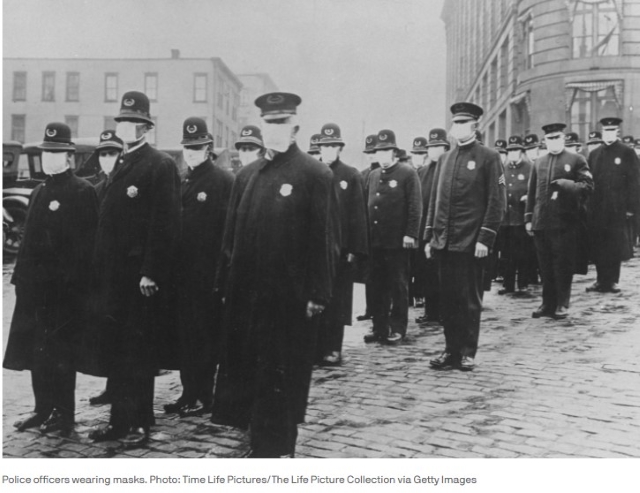

Not wearing a mask was illegal in some parts of the country.

Babe Ruth returned to his hometown of Baltimore after the season ended and came down with the flu again.

Unlike today's virus, there were no asymptomatic cases. You felt very sick within ~24 hours, so healthy-looking people weren't considered a threat to one another.

The bottom line: Overall, 60–70% of flu-related deaths occurred between late September and late December. Cities that took precautions early were able to "flatten the curve" and slow the death rate, while cities that reacted late were not.

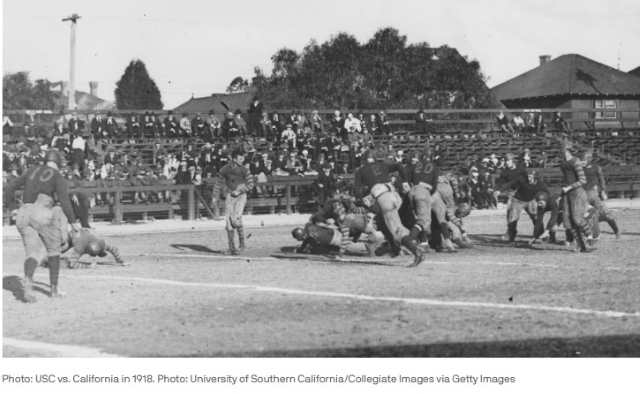

8. A football season cut in half

As the second wave ravaged the country, hitting young adults particularly hard, the college football season petered out, with teams struggling to field rosters and schedule games.

By the numbers: Most teams played five games or fewer, and entire conferences shut down. By the start of November, just 87 college games had been played nationwide, compared to 253 one year earlier.

Michigan (5-0) and Pittsburgh (4-1) were named co-champions, with the former shutting out an otherwise-unblemished Syracuse team while the latter crushed previously unscored-upon Georgia Tech.

Game of the year: The above-mentioned tilt between Pitt and Georgia Tech was organized as a War Charities benefit and included a who's who of football legends: sportswriter Walter Camp was in attendance, while head coaches John Heisman (Georgia Tech) and "Pop" Warner (Pitt) roamed the sidelines.

The big picture: Even before the pandemic cut the season short, football's place in American culture had begun to transform that fall thanks to the advent of the SATC (Student Army Training Corps), which allowed students to begin their military training on campus.

"As top college athletes enlisted in the war efforts and universities struggled to find enough bodies to field teams, more players who otherwise wouldn't have had the opportunity to play at the college level were given a chance to participate. The sport became less of an elitist pastime and more of an everyman's game."

— Chantel Jennings, The Athletic

9. The third wave and the lessons to be learned

Imagine for a second that COVID-19 has stopped wreaking havoc across the globe and health officials have said that it's safe to resume ordinary activities.

That's what happened during the last months of 1918. And that's how the third wave of the influenza pandemic began.

The Great War had ended, and the deadly pandemic had seemingly run its course — but the virus was still lurking.

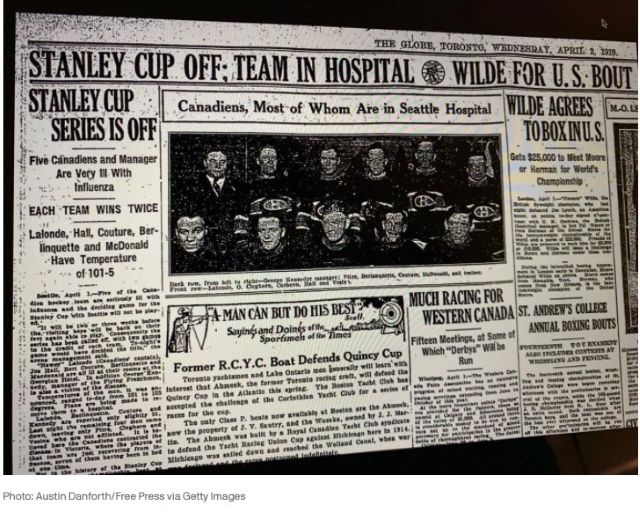

On April 1, 1919, the puck was set to drop on Game 6 of the Stanley Cup Final between the Seattle Metropolitans and the visiting Montreal Canadiens.

But that morning, all but four Canadiens came down with the flu, causing the game — and series — to be canceled (both teams were later engraved on the Stanley Cup above the words "SERIES NOT COMPLETED").

On an even more crushing level, 37-year-old Canadiens defenseman Joe Hall, one of the NHL's most decorated veterans, passed away two days later.

Meanwhile, in Paris ... President Woodrow Wilson fell ill so suddenly at the Versailles Peace Conference that his doctor thought he'd been poisoned in an assassination attempt. In fact, it was a severe case of the same strain of influenza.

The bottom line: At some point in the next few months, leagues and offices will clamor to re-open and citizens will be eager to return to normalcy. When that time comes, it's worth remembering the dangers of the "third wave."